By default, the mascot of the fantasy genre is the Dragon, with their understudy the unicorn in a close second place. This post will look at the history and meaning of dragons in both sci fi and fantasy styles of fictional content.

Joseph Campbell’s Hero with a Thousand Faces identifies the dragon as the ultimate nemesis, encountered at the darkest hour of the hero’s journey in a dark abyss within the earth. Representing great power, the dragon is a universal symbol found in cultures around the world throughout human history.

The dragons of medieval European mythology where typically large winged fire breathing monsters that inhabited caves, castle dungeons or other lairs. Evil dragons where the antagonists of fairy tales to be slain by the hero, while the rarer good dragon gave the hero advice or other boons to help them on their quest. One well known European legend is that of St. George and the Dragon, first told in the tenth- or eleventh-century, where a mounted knight is sent against a dragon with an insatiable appetite. This tale would go on to inspire the 1981 film Dragonslayer.

A notable dragon in fantasy literature from last century is Smaug, from J.R.R Tolkien’s The Hobbit. Smaug, whose name is clearly social commentary on the air pollution side-effect of modern industrial society, sleeps on a large horde of treasure deep within Lonely Mountain.

Asian dragons, in legends and folklore are more commonly wingless and snakelike, symbolic of magic, power and luck rather than the dreaded behemoths found in European mythology. Unlike their European counterparts they have no wings, but can still fly using mystical abilities. There were three tiers of asian dragons, each differentiated by the number of claws on their four legs. The five-claw dragon was associated with the Emperor, four-clawed dragons were associated with nobles, and three-clawed were the symbol of ministers and commoners. Interesting to note that higher ranked dragons were closest to humans in terms of hand anatomy. They were represented holding a fiery pearl in one claw, although this was more a symbol of spiritual power and wisdom than of wealth or treasure. Dragons have been part of Asian culture for over 7,000 years.

Dragons are also found in sci fi, although not as often as in mythology. Early examples include the blue fire-breathing Godzilla and King Ghidorah from the 1964 kaiju monster movie. King Ghidorah, commonly known as Ghidrah in the West, had three heads, two tales, lacked arms but had massive wings which could cause hurricane level winds. He could also breath ‘gravity beams’ of yellow lightning from each of his three heads.Ghidrah was gold in color, originating from Venus, and represents one of the first incarnations of dragons in the sci fi genre.

A few years later in 1968, writer Anne McCaffrey penned the sci fi fantasy Dragonflight, the cover of which bears a remarkable resemblance to a single-headed version of Ghidorah mentioned in the last paragraph (see illustration). Dragonriders of Pern takes place on another planet and features a pre-industrial society divided into four classes. One of these, the Weyrfolk, rides a genetically engineered breed of psychic dragons to combat the Thread, an extraterrestrial pestilence. The Dragonriders of Pern series consists of 22 books, still wildly popular and has won awards including the Hugo and Nebula awards.

More recently (1980’s), the TV series V had an extraterrestrial race who appeared to be benign humanoids but where indeed reptilian beings intent on harvesting earth people for food. Also from the 1980’s came the film The Last Starfighter, the supporting role played by a friendly reptilian starfighter pilot.

From the ever entertaining field of conspiracy theory has many accounts of shape shifting reptilian aliens from the Draco constellation. Author David Icke, in his book The Biggest Secret, suggests that a race of reptilian aliens from the Draco constellation control world governments in secret. Icke’s concept of shape shifting dragon men who inhabit the inner earth bears resemblance to author Robert E. Howard’s ‘serpent men‘ from the King Kull stories published as The Shadow Kingdom in Weird Tales, 1929.

Dragons in sci fi, fantasy and science fantasy genres represent pure wonder. The European dragons typically embody the lowest depths of fear, the hero’s nemesis, and the all the worst human sins including greed, lust and avarice. It is fascinating how different this symbol is compared to the dragons of Eastern philosophy, which stand for the apogee of human potential such as Kundalini awakening in the East Indian Yoga tradition, national leadership in China, and wisdom and creativity in all Eastern cultures. As I write this, there is a large lizard on the cinder block wall outside my office window, now sunning himself and doing pushups. This article is dedicated to you, little dragon.

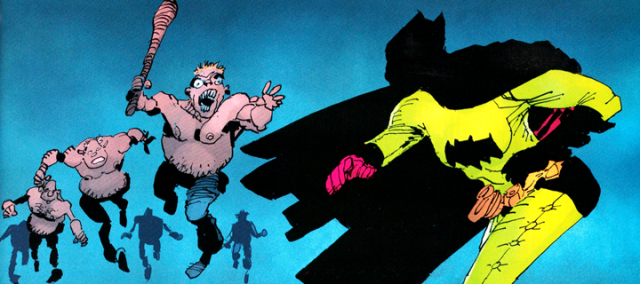

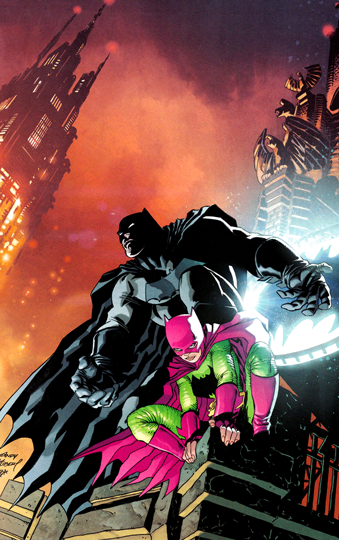

This post is a review of Frank Miller’s Dark Knight Universe and the third installment in the critically acclaimed series,

This post is a review of Frank Miller’s Dark Knight Universe and the third installment in the critically acclaimed series,